STORIES OF SCHOLARSHIP

My work as a scholar is reading, writing, and communicating knowledge. Here’s some more about that.

NOMADIC KNOWLEDGE

/nōˈmadik/ˈnäləj/ ::

The stop, go, and flow of knowledge transaction that is discontinuous, spontaneous, and more or less important for the time being, or later.

Why chose a straight line when you can be a dynamic and expansive?

︎

Dissertation Update

Things I care about in my Dissertation >>

The historical and continual importance of assigning a national label or transnational co-production labels to an (animated) short film.

Like in the list below of prize nominees from the 2021 edition of Premios Quirino de la Animación Ibero-Americana >

Image: Animated Short Film Prize Nominees, 2021: www.dessignare.com/2021/02/los-premios-quirino-de-la-animacion.htm

Q: What is the power of that national label on a global scale, and where does it come from exactly?

When looking at the prize lists of Ibero-American animation in the link, there is clearly a focus on announcing the film's nationality and co-production partners. Well, why is that there, and what's the story behind it?

The answer to this is not simple, not consistent, and highly dependent on factors like accessibility to technologies, regional and (trans)national economic systems for independent filmmaking, and even personal stories of the filmmakers and producers involved.

Folks think of metadata as a self-evident label of truth, but it's often highly subjective and quite revealing when more nuanced interrogation sare explored:

1) Funding Sources; 2) Settings and Locations; 3) Languages used & Subtitles available; 4) Origins and Migrations of Producers; 5) Origins and Representations of Protagonists; 6) Narrative Content in the Film;

7) Viewer engagement and Movement via Shares of a digital object on the Web.

My dissertation explores national metadata in more depth, and how the shifting landscape of the Web at the onset of YouTube, Vimeo, Facebook, and other Social Media platforms mobilized independent short filmmaking and animation in the Spanish-speaking world. Nevertheless, their presentation on the Web leans into national constructs.

Why? The story is in the metadata.

Upcoming

Publication

Publication

Cyborg Citizenship in Keiichi Matsuda’s Colombian short film,

Hyper-Reality (2016)

A book chapter in Digital Encounters in Latin America now under contract at University of Toronto Press and pending publication in 2021.

The volume is edited by Dr. Cecily Raynor and Rhian Lewis.

![]()

I found London-based, Japanese director, animator and architect, Keiichi Matsuda’s Colombian short film, Hyper-Reality in the Fall of 2016 while I was teaching Intro to Spanish in Athens, Georgia.

Short films are priceless teaching tools because they’re short, intense, and steeped in cultural relevance.

This short film frankly blew me away.

I immediately found a way to work it into my lesson plan around Halloween since it was interestingly tagged as a “horror film.”

When I showed it to my students, they had widely mixed reactions:

fascination, horror, confusion, sensory overload, enthusiasm

While it seemed very sci-fi at the time, I had a sneaking suspician that this was merely a speculation of the very clear course that we are currently on - at hyperspeed.

My own enthusiasm about this short film wasn’t just about the content itself, but the very interesting production story behind it.

It IS a Colombian story, in a way, but it’s also the story of how an Internet can help a very smart person in London go and meet some visual storytellers in Medellín, and then go back home and fundraise online to make a film back in Colombia, and then go back to London and postproduce and animate the whole thing and then get some big attention for it all over the world as a result.

I had a big, long phone call with Keiichi Matsuda (the director) in April of 2019 when I was turning this paper into a full-fledged publishable piece, and I asked him how he felt about seeing it as a Colombian film. He was kind of surprised by that, but didn’t entirely disagree.

Regardless of what he or anyone else thinks, I found that the highly transnational and technological method of making this short film was not a side-note or a disconnection of the actual story.

It’s a continuation of imagining how we have been and are going to continue living a hybrid life between the increasingly indistinguishable realms of the analogue and the digital as cyborgs, posthumans, technologically-dependent humans, whatever you want to call it.

It’s a film that reminds you that wherever you are, the governing forces behind the Internet (aka marketing) is constantly augmenting your space, your decisions, your motivations, and your perceptions of self. Could you opt out? Even if you wanted to?

![]()

I’m so grateful to both Cecily & Rhian for their tireless work and efforts to make this volume a reality, and I’m honored that my work will appear alongside seasoned cyberculture scholars such as Eduardo Ledesma, Carolina Garza, Norberto Gomez, Thea Pitman, and others.

* I’ll link the anthology when it comes out in print!

Publication

Re-ordering material hierarchies in Jossie Malis Álvarez’s animated short film series, Bendito Machine (2006-2020)

A book chapter in Pushing Past the Human in Latin American Cinema, edited by Carolyn Fornoff and Gisela Heffes, SUNY Press: Publication forthcoming in 2020

This book chapter was born from the perfect storm of my course with animation expert, Dr. Richard Neupert on History of Animation and finally starting to understand what the heck is "Object Oriented Ontology" (OOO).

While learning more about animation, I started to feel very much that the principles behind animation connected deeply with the notion that objects and nonhumans can act and have agency (depending how you look at it). According to OOO, this is an ecological breakthrough by stepping outside out human-centered worldviews and considering what sentient and "non"-sentient beings do without us around.

I had come across Jossie Malis Álvarez's work in the past when I was organizing short film festivals, and had always kept an eye on his work which tended to be quirky, humourous, yet deeply ironic and pessimistic about the future.

(See the image for his aesthetic which is a great reference to the old-school animation of Lotte Reineger's Adventures of Prince Ahmed (1926) with its cut-out silhouettes, colourful backgrounds, and close relationship with soundtrack and sound effects).

When I saw his crowdfunding campaign for another episode of his short film series, Bendito Machine, I quickly saw how another example of how animation can present ecological arguments and premises just as well as live-action films can. Do we need to see the literal wreckage all the time? Can we play out our speculations and the worst-case-scenario through animation? That's exactly what each episode of Bendito Machine does, and the 6 episodes altogether (from 2006-2020) present cyclical narratives that condense time, space, and cause-and-effect in a way that only cartoons can pull off. It's called suspension-of-disbelief, and we all set aside our material logic to ride the magic carpet thanks to animation.

Well, a term paper turned into a conference presentation at the Southeastern Conference of Latin American Studies (SECOLAS) at Vanderbilt University in Spring 2018, and, in the meantime, I had sent out my abstract to the CFP posted by Carolyn Fornoff and Gisela Heffes. Almost two years later, we've got a final revision and a signed contract.

Publication

Was it all a Dream?: Chicanx Children and Mestiza Consciousness in Super Cilantro Girl (2003) and Tata's Gift (2014)

A book chapter in Voices of Resistance: Essays on Chican@ Children's Literature, edited by three professors from Cal State Fresno, and published by Rowman and Littlefield in 2018. Felipe Herrera, Chicano author and U.S. National Poet Laureate, has written the introduction for the edited volume.

![]()

I started my career teaching Spanish in grade schools (elementary, middle, and high school), and found that some of the most effective ways to teach language and culture was through storytelling. Finding authentic stories by Latinx and Latin American authors to present to my students was my priority, yet it was surprisingly difficult to find literature in Spanish or Spanglish that was not a direct translation of “mainstream” children’s classics. This has been changing for several years now, and it’s even really awesome that my uncle, Pablo Cartaya is an award-winning Latino young-adult’s author.

Years later, in a graduate course at University of Georgia on Multicultural Children’s literature, I started developing ways to critically engage with books and media that were “meant for kids,” but in fact needed to be taken quite seriously as political activism through dreaming, expression, play, and radical action.

Working on this project could not have come at more critical time when controversial legislation that targeted Chicanx and Mexican American youth began cropping up including the Ban on Tuscon, Arizona’s Ethnic Studies Curriculum, and the increasing visibility of DREAMers and DACA recipients while deportations happened everyday.

The great Gloria Anzaldúa’s words echo in my mind:

“Caminante, no hay puentes, se hace puentes al andar.”

This act of bridging worlds through movement -- across lands, between dreaming and reality, humans and nature, magic and technology -- this notion is narratively and visually developed in both of the works that I wrote about that are part of the multicultural children’s genre: Super Cilantro Girl (Juan Felipe Herrera) and Tata’s Gift (Dionisio Ceballos).

I presented a conference version of my term paper at the Crossroads: University of Georgia Graduate Research Conference, and then I was sent the same Call for Papers by about 3 different people who said, “This sounds like you!” When it knocks - more than once - answer! I did. A year and a half later, I saw my words in print alongside an impressive collection of essays about Youth Activism, Pedagogy, and Chicano Children’s literature. I was honored as well that the author of Super Cilantro Girl, Juan Felipe Herrera, wrote the introduction to the volume. I imagine him reading my analysis of his work, and hoping that it kinda made him smile a bit.

Unpublished sample

Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent (2015):

Filmic and Journalistic Narratives of Exoticism and Colonialism in the Colombian Amazon

In the Spring of 2016, I made a trip to Asheville, North Carolina --

– a small city in the heart of the Blueridge Mountains in the Southeastern United States. I had just returned from spending a few weeks in the Peruvian Amazon, and a friend recommended that I see Colombian director, Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent (2015) due to its global success that had made its rounds in the international festival circuits by then. As I did not have a clear plan for my evening, I casually searched for a showtime in the area, seriously doubting that I would find a theater that would show a Colombian arthouse film. In fact, I did find a listing in a small theater on the outskirts of the Asheville area. When I arrived at the cinema that evening, the marquee listed two titles in bright red letters: Embrace of the Serpent, and then the title of some other movie which contained the three letters: XXX at the end. I realized that this “independent cinema” hosted theaters that screened pornographic films alongside arthouse features. It did not help either that I was watching a movie called Embrace of the Serpent, a damning title that would make it difficult to explain its high-culture value after winning prizes at Cannes, Sundance, and The Academy Awards. Here I stood at the convergence of high art and smut in the middle of Appalachia, and this patchwork of cinematic margins perfectly reflected the global and local communicative processes that brought these films under the same roof. Layered behind the glowing title, Embrace of the Serpent, were the numerous communicative discourses of press and publicity, film reviews, interviews, audiovisual journalism, and material production details that carried this highly-regionalized Colombian film into the most prestigious spaces of global cinema.

Situated between anecdotal, journalistic, and cultural analysis, the communicative approach of this work on the success of Ciro Guerra’s award-winning film, Embrace of the Serpent (2015) examines how a black-and-white film made in the Colombian Amazon aimed to criticize and overwrite colonial practices yet fell into the historical patterns of exoticism and exploitation in the postlude of the film’s global success. Between 2015 and 2016, the film’s circuit of nominations among high-profile festivals generated a journalistic buzz by popularized western and English-language online sources such as IndieWire, Vice, The Guardian, The New York Times, and NPR. The numerous articles featured interviews with the director as well as the indigenous protagonists, Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolívar Salvador, who were commissioned as non-professional actors on-site in the remote jungles of Vaupés, Colombia. While the content of the film depicts the clash of worlds between white, western, male scientific explorers and native locals with magical cosmologies, knowledges, and mistrust of outsiders (reminiscent of 19th century exploits), Guerra claimed in interviews that the entire production aimed to collaborate with local tribes and their approaches to the project rather than reigniting colonial practices the film was aiming to expose. Following the global success and attention of Embrace of the Serpent as a symptom of new possibilities in Latin American cinema, Colombian press and academic analysis questioned the continual commitment and collaboration between the production team and the space and resources used for the film, including natural catastrophe that affected the villages who participated in the film as well as the financial abandonment of Nilbio Torres, who has since not continued a career in acting but is known to be collecting tickets in a regional museum as of 2016. The problematic history of filmmaking in the Amazon and its resurgence in Embrace of the Serpent exposes how filmic and journalistic exoticism of indigenous actors and collaborators exemplify the colonial practices of the film industry operation from pre-production to the postlude of global success.

This work will approach analysis in two layers: firstly, by connecting the content of Embrace of the Serpent with historical interventions of the Amazon; and secondly by examining the journalistic coverage of the film in its ascent to international success as well as in its aftermath. The main question at work in this two-fold approach is whether filmic practices in the Amazon could exemplify ethical partnerships when national and international discourses come into play during promotion and festival prize circuits, and the necessity to carefully consider the historical interventions of filmmaking and their long-term effects on indigenous populations.

Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

Almost entirely in black and white, Ciro Guerra’s third feature film is set in the remote Amazonian regions of Vaupes, Colombia (the southernmost interior province bordering Brazil). The two timelines set nearly forty years apart are loosely based on two early 20th century scientists: German ethnologist, Theodor Koch-Grunberg and North American biologist, Evan Schults (acted by Jan Bijvoet y Brionne Davis). The main protagonist of the film, however, is the powerful shaman of the fictitious Cohiuano tribe named Karamakate (acted by Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolívar), who is asked by both scientists to lead them to the mysterious medicinal plant called la Yakruna. The search for the plant in both timelines connects both scientists and their need for physical and psychological healing as well as a visual chronicle of neo-colonial interventions in the Amazon such as the rubber extraction industry and Catholic missionary sites. Between the earlier timeline with Theo and the latter one with Evan, Karakamate’s faded memory of his previous knowledge of plant medicines and navigation in the jungle is slowly recuperated as he retraces his steps from forty years prior. Aside from the arthouse aesthetics of the film which provide a surreal and dramatic quality to the viewing experience, the plot is packed with references of historical interventions in the Amazon and the numerous failed attempts to conquer, civilize, document, and communicate Amazonian realities and knowledges to the outside world.

Among them, a direct reference to Werner Herzog’s film productions in various sections of the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon during the making of Fitzcarraldo (1982) and Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972). In a scene between Evan and the elderly Karakamate, Evan’s luggage must be lightened and thrown out of the boat to which he reluctantly agrees except for his prized record player and operas on vinyl. After the native shaman examines the vinyl curiously, Evan proceeds to set the needle down and plays Haydyn’s “The Creation” oratorio against the backdrop of the Amazon River and scenes of its dense forestation. This is clearly a nod to Fitzcarraldo, Herzog’s film about an Irish rubber baron who is determined to build an opera house in the Amazonian wilderness at any cost, including pulling a massive steamship over a mountain. The seemingly bizarre imposition of opera in the Amazon is not a fictitious one since Opera houses did exist in places like Manaus, Brazil – run by wildly wealthy rubber barons from abroad. This reconstruction of high art in the remote margins of the world points to theoretical discourses of situated cosmopolitanism in Latin America that David Thompson defines as a “transgressive practice caught between local conflicts and global cosmopolitics” (Luna and Meers 73). In other words, the scene between Karakamate and Evan in which they both listen to the opera in the jungle is a two-way transgression between the outsider in the jungle and the outsider in the opera. While this meeting of minds between Karakamate and Evan during the film seems generally harmless and collectively cathartic, several other scenes in the film recreate the horrors of colonial interventions in the Amazon – and attempt to project them from the perspective of the indigenous protagonist, Karakamate.

Filmic Invasions in the Amazon as a continuation of historical colonialisms

Historically, the interior Amazon regions of South America have been precarious sites of conquest from outsiders who hope to capture the landscape in their representations. Yet, global fascination surrounds the Amazon and its exotic reputation as a treasure trove of secrets, purity, virginity, temptation, chaos, madness, and danger. Countless cultural products reflect this across colonialization, literary and art movements, and into the global filmmaking era. Since the first explorations in the early 16th century beginning with Friar Gaspar de Carvajal’s documented voyage, subsequent journeys into the pre-conquest Amazonia were committed to commercial exploitation of the region (mainly in search of gold like Pizarro’s exhaustive search for the mythical El Dorado). After hundreds of years of political and religious colonialism and the decimation of Amazonian native populations came the next wave of explorations by Victorian naturalists in the 18th until early 19th centuries. These ethnographic explorers like von Humboldt, Agassiz, von Martius, Spix, and Condamine (18th century) followed by Spruce, Wallace, and Bates (mid-to-late 19th century) produced documentation of the Amazon through scientific and didactic discourses – complete with drawings, woodcuts, engravings that depicted native peoples, flora and fauna in the Amazon (“A Naturalist’s Paradise,” Hemming). Scientific explorations continued into the 20th century with self-possessed scientific explorers like Hiram Bingham’s uncovering of the remote and well-persevered Incan ruins in 1911 (now known as the world-famous Machu Picchu) and ongoing research expeditions for medicinal plants and remote peoples such as the two scientists of whom Embrace of the Serpent is loosely based: Theodor Von Grunberg and William Evan Schults.

Moving from the 19th into the 20th century, photography and filmmaking became technological mediums through which to project Amazonian sensationalisms, broadcasting fetishistic images that postulated the Amazonian native as pure and innocent Noble Savage/ a dangerous and bloodthirsty cannibal (Nugent). Not far from Amazonia itself, South American intellectual elites their prospective cultural movements sought to reclaim the wild landscape and its indigenous populations into their prospective national discourses. Brazilian modernist movements during the global avant-garde era created allegories of cosmopolitanism and cultural production such as the appropriation of the Tupi cannibal in Oswaldo de Andrade’s Manifiesto Antropófago (1928). In the satirical manifesto, Andrade champions the Tupi native and his consummation of the European colonizer, thus adopting his characteristics and manifesting the hybridity of a cosmopolitan body – regional and global at once. In the mid-20th century, experimental filmmakers during Brazil’s Cinema Novo movement realized Andrade’s cannibal figure on the big screen in films like How Tasty was My Little Frenchman? (dir. Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1971).

The up-and-coming field of Anthropology in the 20th century brought a new wave of scholars and fieldworkers into the Amazon such as Napoleon Changon’s globally-famous text, Yanomamo: The Fierce People (1984) and the videos that accompanied his anthropological research. Global fascination with Amazonian populations like the Yanomamo who were “untouched” by the outside world brought the margins into the global imagination of New Age “back to nature” movements and celebrities of world music like Sting who sang their praises. Interestingly enough, a string of B-quality tropical/horror exploitation films in the 1980s with titles like Cannibal Holocaust (1980), Cannibal Ferox (1981), Eaten Alive (1986) feature similar plotlines of outside scholars whose contact with remote tribes in the Amazon turn into deaths by cannibalism (Scoping the Amazon, Nugent). Meanwhile, Indigenismo literature produced in countries that contained Andean and Amazonian regions dramatized the clash of race, social class, and allegories of nationhood in novels such as Jose Eustasio River’s La Voragine (1924) , Juan Leon Mera’s Cumanda (1877), Clorinda Matto de Turner’s Aves sin nido (1889), and José Maria Argueda’s Los rios profundos (1958). And finally, throughout this entire timeline, the Amazon endured an industrialization of the resources found there – most notably the Amazon Rubber Boom at the turn of the 20th century in which horrific labor exploitation meant the deaths and tortures of native populations. Other forms of extraction practices and mining meant the privatization of land, debt creation, and hierarchical infrastructures of global capital and mechanization of labor – thus bringing the most destructive forms of capitalism into the heart of the Amazon.

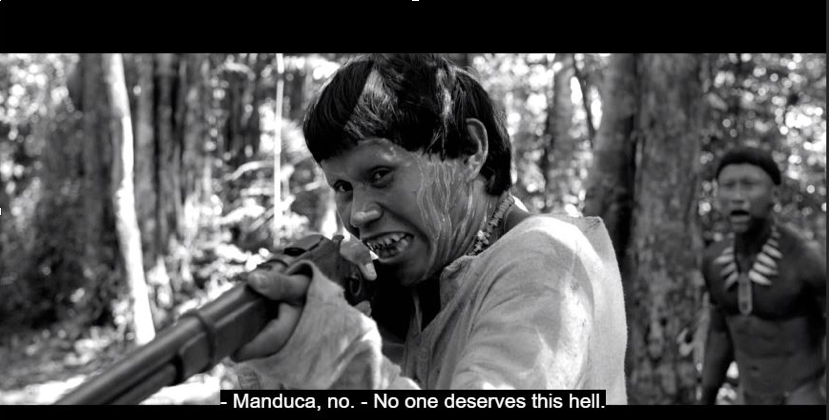

The two timelines in which the scientists encounter Karakamate are deliberate since the thirty years between Theo and Evan’s expeditions create a “before-and-after” effects of colonial endeavors in the Amazon – specifically those of the rubber extraction industry and of religious missionary sites. In Theo’s timeline, for example - their arrival to the Catholic missionary showed young indigenous children being whipped and shamed for speaking the “devil’s tongue” (their native indigenous languages), and when the missionary is re-visited in Evan’s timeline, the space has become transformed into a site of messianic evangelism. The disciples of the self-proclaimed Messiah are full-fledged adults and may very well be the same children that were living there in the previous timeline. Both times, the travelers must convince the disciples of their worthiness – in the earlier timeline, they must prove that they are not searching for caucho (rubber), and manage to convince the Cappuccino priest by reciting biblical phrases while faced with the barrel of a shotgun (Image 1); and in the later timeline, the cunning Evan affirms that they are the wise men from the Orient who have come to bring gifts (Image 2). In both cases, the hostility towards a scientific and indigenous coalition indicates a colonial space of religious extremism and defense of resources in the jungle.

Image 1: Theo explains the expedition (56:34)

Image 2: Evan confirms that they are Wise Men (1:11:14)

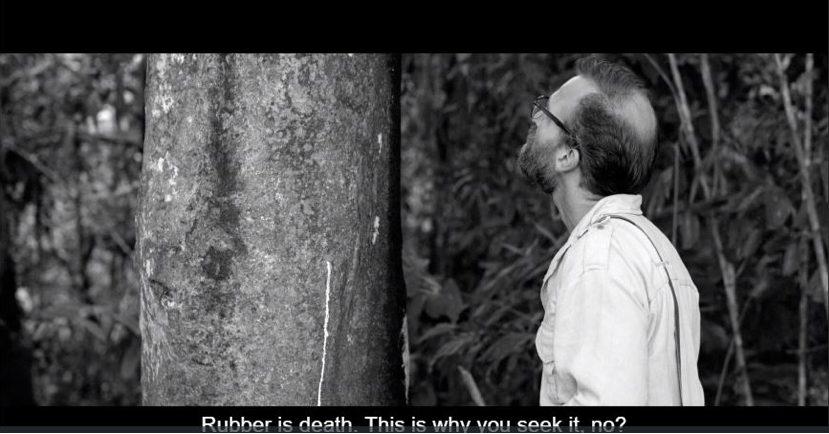

In the case of the Amazonian rubber industry, Theo, Karakamate and Manduca (Theo’s indigenous, German-speaking companion) come across a graveyard as the camera pans over to a grove of rubber trees that are dripping the white, milky substance. In a traumatic rage, Manduca kicks over the buckets filled with the pre-processed liquid rubber. A mangled and dismembered man desperately tries to scoop the rubber back into the buckets while screaming and pleading for the three men to end his life. Not meeting daily rubber quotas meant further torture, so Manduca fetched a shotgun to end the man’s life against the wishes of Karakamate and Theo (Image 3). Finally, to puncture this climactic moment, Manduca fires the gun but deliberately misses. In the latter timeline, Evan and Karakamate dock their boat on leafy shoreline while Evan examines a map. Distracted by markings on a rubber tree that are nearly faded, Evan approaches the tree and stabs it with a knife until the tree reluctantly bleeds the white and milky rubber. Karakamate observes Evan from behind and asks warily, “Are you interested in rubber?” Evan responds scientifically and says that he has never seen this species of rubber tree before. Karakamate declares, “Rubber is death. This is that why you seek it, no? You are two men” (Image 4). Here, the elder Karakamate is questioning Evan’s scientific approach as commercially motivated rather than a study of plant knowledges like he and Theo discussed during their encounter.

Image 3: Manduca aims to end a man’s misery (38:18)

Image 4: Evan is questioned as he examines a rubber tree (108:14)

Within the plot, Embrace of the Serpent references historical exploitation in the Amazon through two different timelines and the evolution between two neo-colonial moments in the 20th century. In the scenes described above, the white scientists are validators in moments of colonial hostility, yet the indigenous protagonist, Karakamate always has the last word when their motives and disciplines are at odds.

Cinematic Margins – the Nationalization of Cinema on the Global Stage

Despite the clear connections between specific moments in the film and historical events and persons, the global press reception of Embrace of the Serpent took on another life of its own as an example of a burgeoning Colombian film presence among the “big three” nations of Latin American Cinema: Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil. The Oscar-nominated film initially received funding from the Cinema Development Fund (Fondo the Desarrollo Cinematografico – FDC), but experienced difficulties summoning European coproduction financial support largely due to the expensive production costs of filming in the Amazon and Guerra’s stylistic choice to make the film with a nostalgic black-and-white palette. Finally, the Ciudad Lunar production house created a funding alliance between Colombia, Venezuela and Argentina in addition to support from Ibermedia, INCAA, and the Rotterdam Hubert Bals Fund. After its release in 2015, while not officially selected for the Cannes Film Festival, its competition of the Quinzaine des Realisateaurs (Director’s Fortnight) earned the film the Art Cinema Award. The film went on to win the Alfred P. Sloan prize at the Sundance Film Festival in 2016, the Grand Jury Prize at the Riviera International Film Festival in 2017, and, among other prizes, it was the first Colombian film ever nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards in 2016. This publicity for director, Ciro Guerra was unprecedented in his previous feature films, and heightened his status as an internationally-recognized Colombian filmmaker that was redefining global media perceptions of Colombia as a country troubled with gang-violence, political corruption, and narco-trafficking.

Cosmopolitan cinematic margins: Prizes, Press, Global Perceptions

But how do the most remote spaces of the Colombian Amazon manage to re-write national discourses in global cinema spaces and media? Here, Felicia Chan’s concept of cosmopolitan cinematic margins is helpful in order to imagine the dialogue between the local margins and the global mainstage of nationalized cinema. Specifically, cosmopolitan cinematic margins are when marginal spaces and characters transition into national symbols in global spaces. Given the nature of national labels in film festivals, protagonists can become global icons and themes can become relevant cultural debates in their prospective nations – no matter how marginal or remote those may be. Maria Luna and Philippe Meers apply Chan’s concept directly to Colombian cinema by declaring that cosmopolitan cinematic margins “imply a transition from exoticism (seen from the outside, as in the gaze of urban directors upon rural territories) to cosmopolitanism (the capacity of belonging everywhere, as in the capacity of the films to gain visibility at international festivals)” (127). In the case of Embrace of the Serpent, the Colombian Amazon and the figure of Karakamate become global reference points of Colombian national identity for the urban cinephile who might attend a festival or attend an arthouse cinema. They continue to contend that “the concept…is in fact very useful on more than one level: not only to interpret a film’s content, narrative and style, but also, and more importantly, to shed light on the changing situation of Colombian contemporary cinema and its current position within the space of international film festivals.”

One of the many communicative limbs of these cinematic margins is through journalistic and press/media channels that framed Ciro Guerra’s film as a symptom of a fresh take the emerging Colombian film industry. Not only did major Western media sources like NPR, Vice, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, praise Embrace of the Serpent for its comeback qualities and its significance for Colombian cinema, but the headlines also postulate Guerra’s film as an arthouse denouncement of historical exploitation of the Amazon. The New York Times article, for example, points out the self-awareness of Guerra’s reference to Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo as an updated critique of the filmic invasion and exploitation of the Amazon. The comparison between the Colombian-born Ciro Guerra and Herzog’s approaches to filmmaking in the region favor Guerra’s methods and his efforts to incorporate local practices into the plot of the film. For example, interviews with Ciro Guerra reveal that he insisted on turning to local practices and cosmologies in order to assure harmonious filmmaking like “asking the forest permission” to create impact. Guerra also worked with local, non-professional actors including Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolívar (the two actors who portray Karakamate). Interviews with both Torres and Bolívar echo the mutual sentiment that the film project was a unique opportunity to portray alternative Amazonian cosmologies in addition to denouncing colonial atrocities such as the brutal treatment of indigenous laborers during the rubber boom. One of the interviews with Bolívar describes how Ciro Guerra attended a special screening of the film in a local longhouse after its award-circuit, and how the younger generations of indigenous locals began to have more interest in learning traditional knowledges and languages based on the portrayal of their environments in the film. Torres and Bolívar also traveled with Ciro Guerra to Cannes and Los Angeles for the festival awards. Bolívar is pictured wearing his customary accessories while Guerra is wearing a 2-dimensional version of a feathered necklace. Even these visual and stylistic promotions in the global press speak to a vision of authenticity from the margins and then the printed representation of it worn by the urban director (Image 5). These production details relayed by American Anglophone media uphold Embrace of the Serpent as a film project in the Amazon done the right way. That is to say that if a film is going to be made in the Amazon, the ethics of that project should resemble the procedures that Ciro Guerra claims in his interviews: highly-researched, low-impact, harmonious with local populations and spaces, and financially equitable for actors.

Image 5: Bolívar wears traditional accessories while Guerra sports a 2-dimensional print