Mapping filmic metadata

Unpacking hidden potentialities within notions of “national” short film

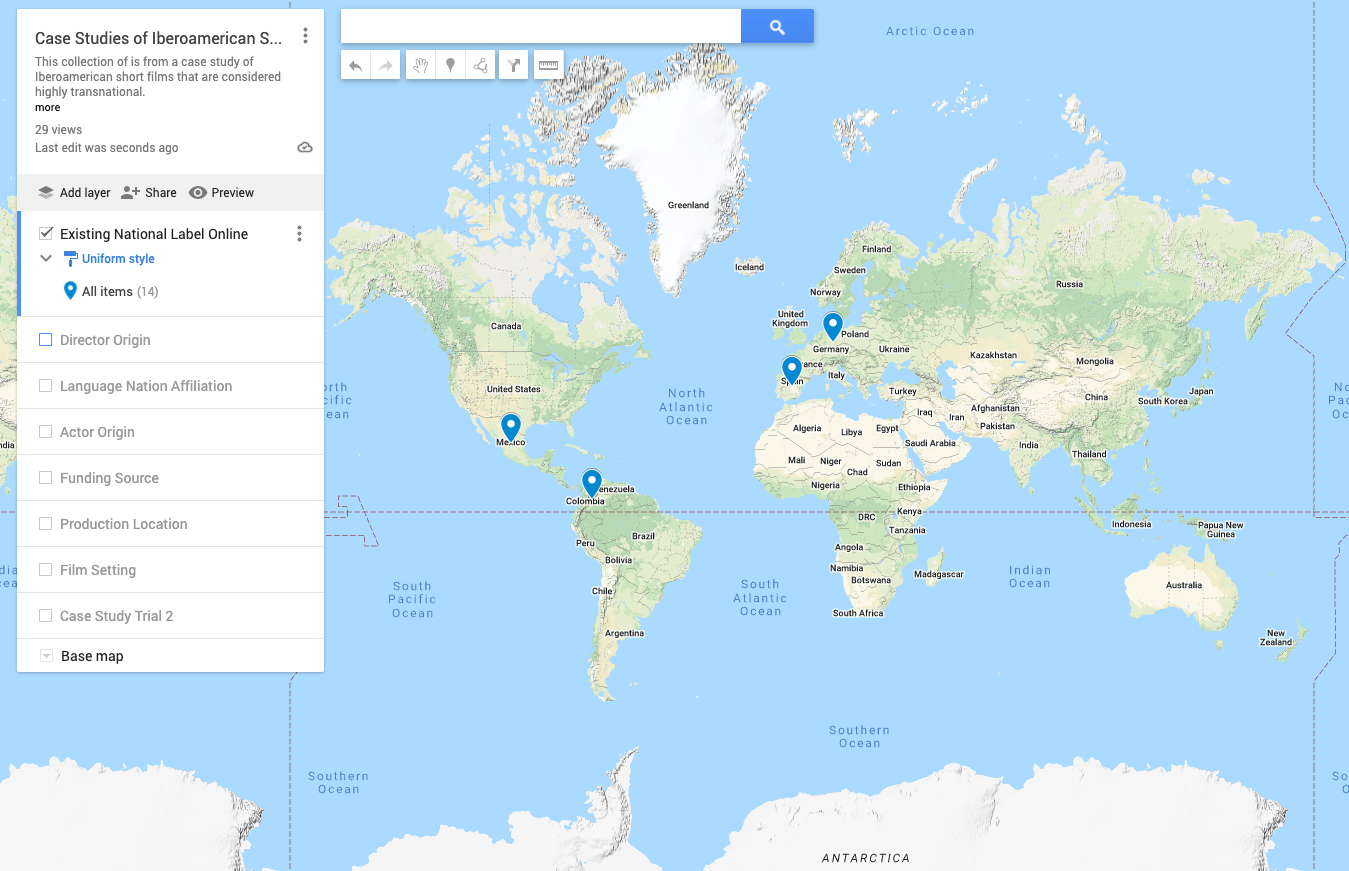

Image 1: the existing national labels of 3 short films online

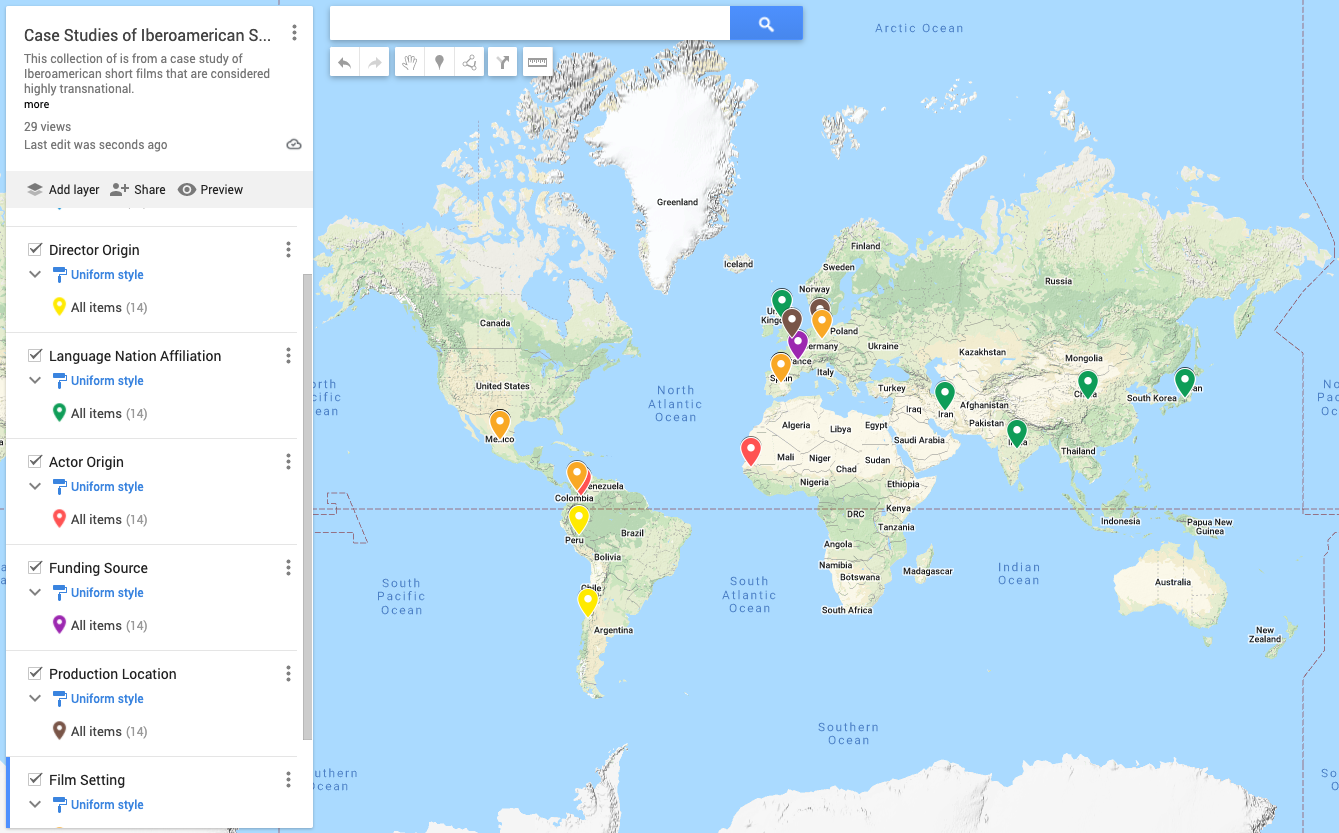

Image 2: (trans)national affiliation of 3 shorts across 6+ metadata aspects

play with map

Lots of descriptors could fill in that blank, but maybe half the time you might use a word that links to some expression of nationality. And we do it by unintentionally recalling the national markers either in the film, around the film, or the national label of that film where you found it.

-

What aligns a short film to a particular nation in the digital age?

- What do those tensions between labels and other aspects of national metadata reveal about Ibero-American shorts during Web 2.0?

Rationale

Surfacing unexpressed metadata is meant to pluralize notions of belonging, territoriality, and the importance of production, content, and the reception of the film itself that is embedded within online metadata that often is reduced to a singular national label.

So, if metadata expressions could illustrate more national potential or pluralize the national affiliation of content and production within short films, colonial dynamics in filmmaking would not necessarily be resolved, but would be more apparent and contextualized for web users who are engaging with content while browsing (streaming) archives, databases, and collections online.

For example, illustrating discrepancies in nationality between funding sources in Europe or the United States and film production labor and location in Latin America would not only create more online access points of metadata in Latin America, but the specific values assigned to one nation or region within the same short film would help clarify colonial power structures that are baked into a singular national label. [i]

Why map metadata?

“Metadata is a map. Metadata is a means by which the complexity of an object is represented in a simpler form.” - Jeffrey Pomerantz [ii]

Metadata and mapping are tightly intertwined theoretically and practically speaking. While granular detail behind the (trans)national metadata of a short film may be difficult to demonstrate on a broad scale, an exercise of cross-examination and annotation is useful to dig deeper into the story of metadata; and, in the case of this study, to specifically locate the metadata.

So, if metadata is a type of map, then a map is also just a more visually recognizable form of metadata.

The first 2 images and map above are of a test sample of three Ibero-American short films that I consider to be highly transnational in both how they were made & how they express themselves as audiovisual narratives. As you probably picked up on, all three shorts expand across the map considerably when taking into account other aspects of national affiliation besides their existing label online.

Three case studies and determinents of national labelling

With the three case study films, their metadata expansiveness was

due in large part to the movements and migrations of the directors themselves,

and the stories that they tell between these national spaces by casting international and multilingual actors.At the end of the day, the most consistent determinant of national labels correlate with the filming location and the institutional funding source.

I did a lot of analysis on the database itself (web analytics, user traffic, key search terms, user-centered tools and praxis) since I was generously handed the data from 2004-2015.

Preliminary conclusions

CDM is a successful website in its volume and variety of shorts, consistent growth, and appeal to Hispanophone user traffic on search engines but the relative absence of short films from outside of Western European and (neo)colonial Anglophone-dominant nations raises questions about how user-curated databases like CDM aim for more web presence from Global South and Hispanophone nations, but end up hosting the usual suspects of dominant national film industries during an era of the Web that was supposed to be even more globally accessible and participative.

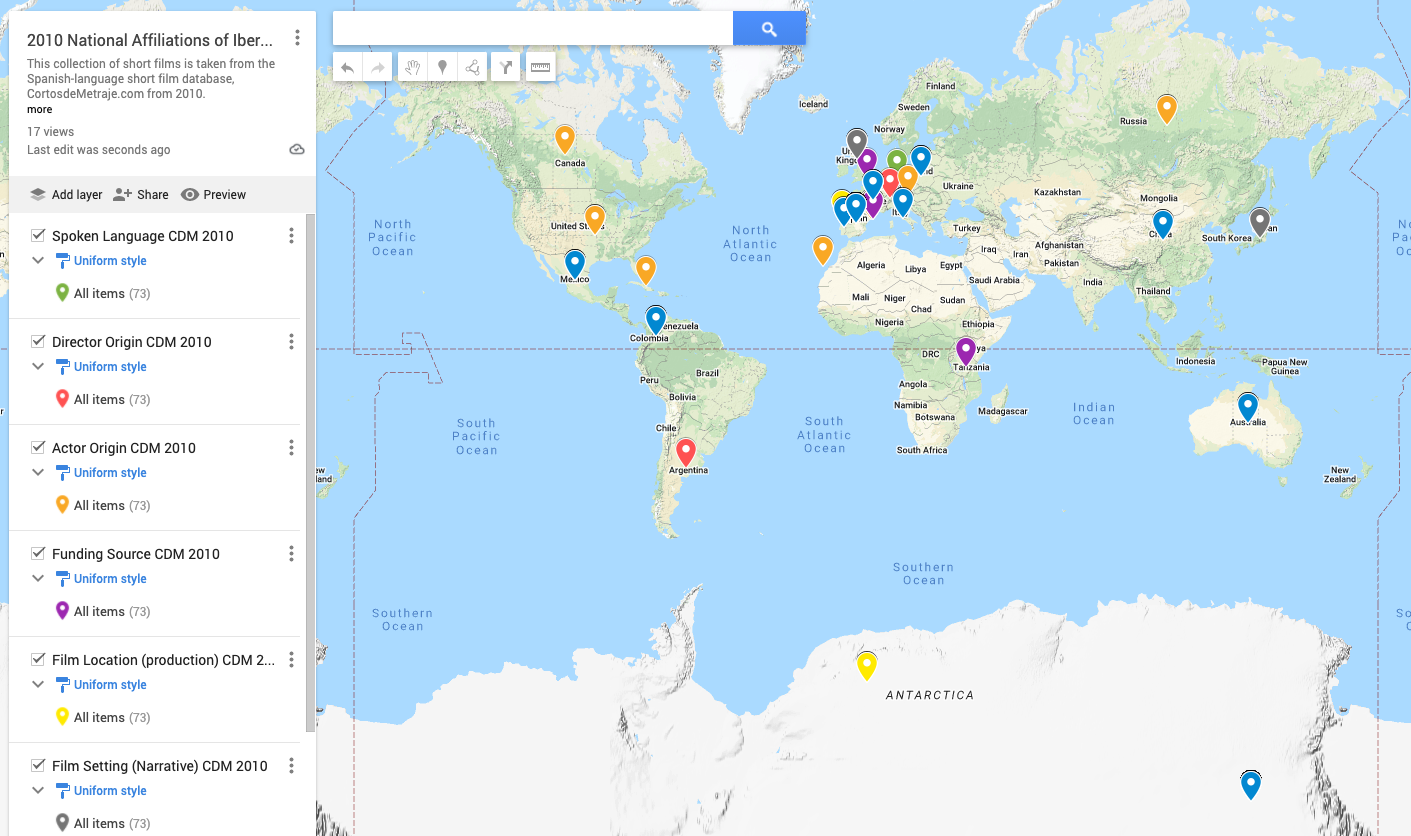

Here’s 2 of my maps of expanded national metadata from my 2010 & 2015 samples from CortosDeMetraje.

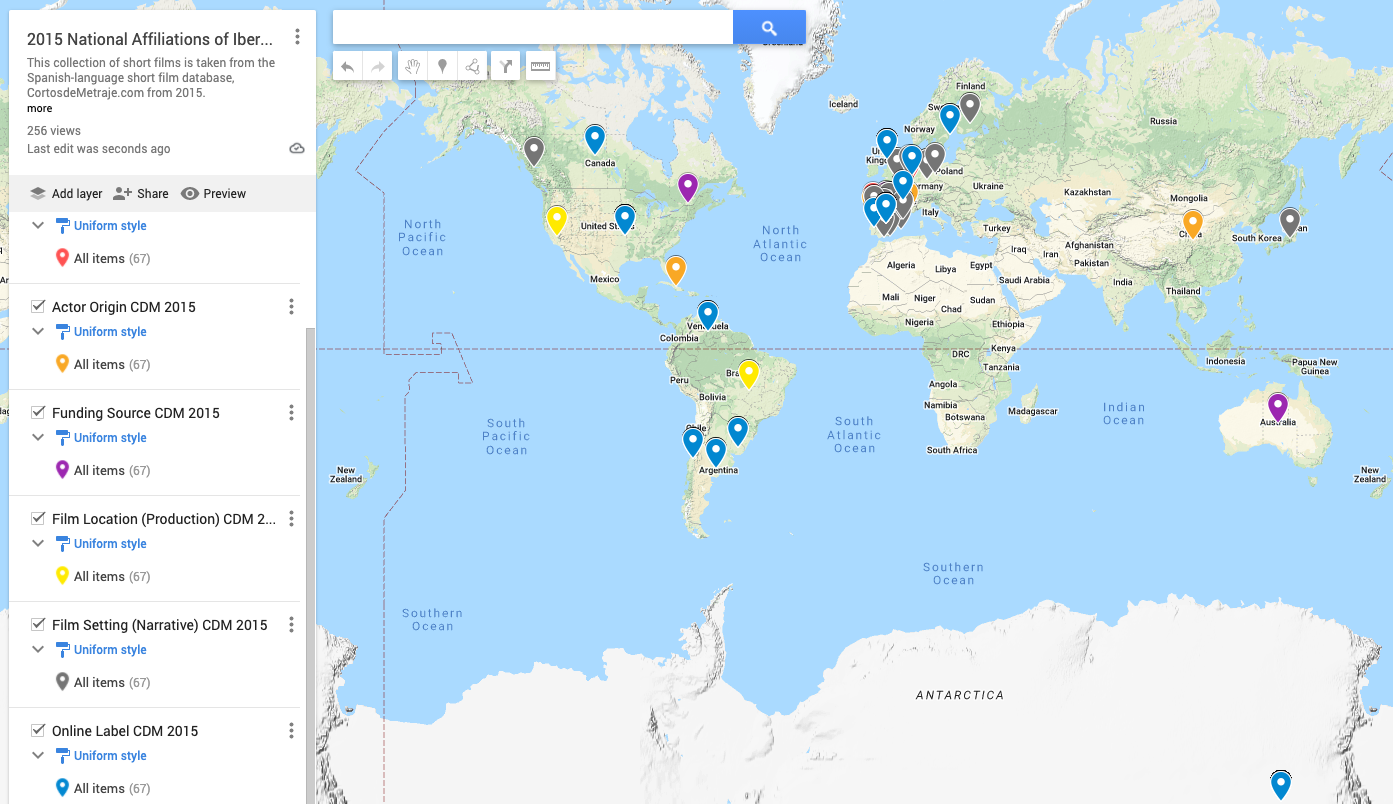

image 4: 2015 sample (50) of shorts on CDM; play with 2015 map

- Except for two films in 2010, funding origins generally do align with short film national labels. Also in strong concordance with the existing national labels on CDM is the territorial location of short film production. So, both funding sources and production locations are heavily tied to the national labeling of short films on CDM across Web 2.0 years.

- A closer look at the 2010 and 2015 maps indicate that the most divergent factors from the given national label of a short film has to do with the national identity of the actors, the languages that are spoken during the film, and, to a lesser degree, the fictional settings of the shorts.

Concerning Ibero-American short film in Web 2.0

While limited budgets and resources for short films might narrow the scope of filming locations and production to a particular nation or region, the (trans)national potential for narrating outside the boundaries of nationhood signal how the Internet age and Web 2.0 ushered forth an era of cosmopolitan digital citizenship in which users can navigate through sites and content across the globe in an instant.

Short films always have a distribution probem since they’re usually exclusive to festival circuits, institutional distributors, or not found in mainstream media channels.

Through identifying how to pluralize and activate more (trans)national and multilingual filmic metadata, I aim to open pathways to continue to examine how historically nationalized cultural products like short films exist and evolve in online spaces that are accessible to more audiences around the world.

What I tried and where we can go from here

Per usual, going against the grain gets messy and difficult to articulate, especially when dealing with software that’s dependent on categoric purities and anglocentric informatics.

So, I got creative, I asked experts for advice, I tested out methods, and I took the most direct path forward regarding my goal which is to show the importance of both content and material when examining the transnational metadata potential of online objects like short films.

So, how can database administrators and online users promote more

plurality and diversity of (trans)national short films that is both nuanced and

accessible?

Look no further than the textual seeds of the Web, metadata. The scales that have been historically tipped toward Anglophone, North American and Western European determinants can begin to incorporate more multilingual and (trans)national searchability for short films that have been largely pigeonholed as institutional national products.

[i] Case in point: Sarah McClennen’s Globalization and Latin American Cinema: A New Critical Paradigm (2018) asks a daring question about one of the highest grossing films ever made of its time: “Is Titanic a Mexican film?” Her interrogation centers around the fact that despite the premise of the film set primarily between the U.K. and the U.S. in the Atlantic Ocean, the predominance of the English language amongst the nearly all-white cast, the production funding from the United States, and the director’s Canadian nationality, almost all the filming locations, manual labor on sets, and (post)production labor took place in Mexico (451).

[ii] See p. 12 of Pomerantz, Jeffrey. Metadata, MIT Press: 2015.

[iii] Cortos De Metraje (CDM) is a plentiful (non-profit, institutional) database (operating out of Málaga, Spain) of Ibero-American short films that features live-action and animated shorts uploaded by users and filmmakers.